Compare & Contrast III.1

To cycle or not to cycle?

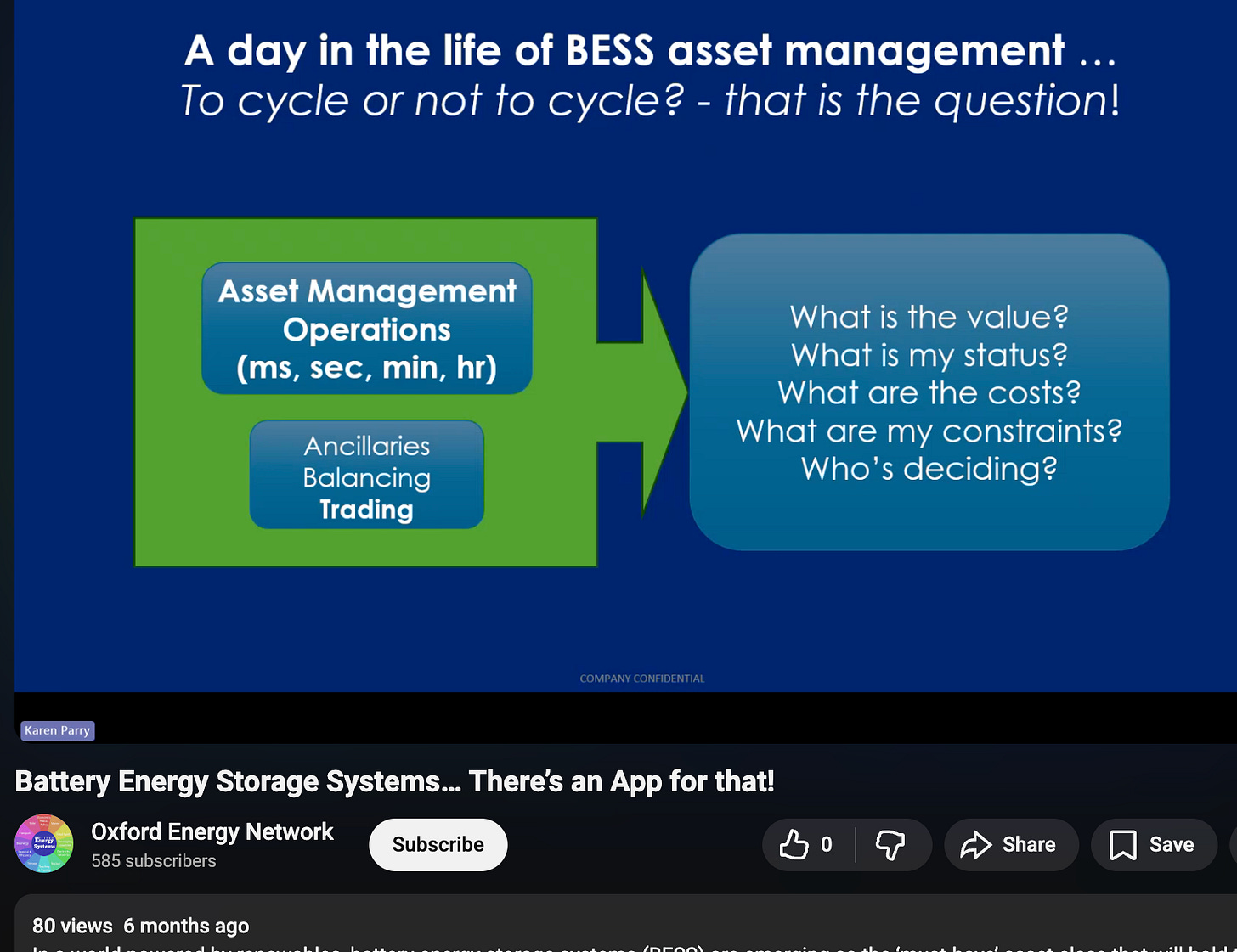

Yesterday I came across a seminar recording that had attracted 70 views over six months. The speaker is Peter Bance, and the event was hosted by the Oxford Energy Network.

The low view count is striking. It suggests that relatively few people are doing sustained research on how flexible assets are actually operated once the press releases fade and the hardware is on the ground.

The talk captures the current state of the flexibility industry with unusual clarity. If this post helps push that video toward 500 views over the next week, it will have served its purpose.

This post continues the Compare & Contrast series. In the first instalment, we looked at optimisers. In the second, we explored virtualisation and structuring, using the ‘smile curve’ to map where value is migrating. This third instalment goes one layer deeper to look at choices for the operating architecture of the asset itself.

From Passive Availability to Active Management

In Germany in particular, the early BESS business model was often defined by passive availability. You bought the hardware, pre-qualified it for the Frequency Containment Reserve (FCR) market, and treated the asset more like a fixed-income instrument than a trading system. Cycling was dictated by grid frequency, revenue was capacity-based, degradation was slow, and operational decision-making was minimal.

In that earlier world, core software requirements were modest. Black-box OEM systems may have been good enough. Some operators might have gotten away with stitching together homemade bespoke solutions for individual sites. The environment was forgiving.

That world is gone… well, duh! you might say, but as we saw in our recent analysis of Gore Street Capital’s reporting, even sophisticated early movers took time to transition away from FCR-dominant strategies.

Today, hitting revenue targets requires savvy participation across intraday and balancing markets. Who is best at managing market volatility against technical complexity?

Germany arrived at this transition later than some other markets. The UK, ERCOT, Australia encountered multi-service, high-frequency complexity earlier, which helps explain why many of the most architecturally ambitious software companies emerged there first. Market structure shapes software evolution.

The Atomic Question

Modern flex-assets are managed in tight, high-stakes decision loops. Yet the core decision remains deceptively simple:

To cycle or not to cycle?

We can call this the atomic question because it is irreducible. Like the “atomic habits” that compound into long-term outcomes, asset performance is shaped by the accumulation of thousands of individual cycle decisions.

A bit like this other atomic question…

Each instance of the question sits at the intersection of three perspectives:

Physics: Is the asset within thermal, electrical, and degradation limits? What does this action imply for state of health, warranty compliance, and remaining useful life?

Economics: Is the current price spread worth capturing? What opportunity cost does this impose an hour from now?

Governance: Is this action compliant with risk mandates, debt covenants, grid constraints, and internal policy? Who is authorised to decide?

In an “easy” market, these perspectives could be loosely coupled. No longer...

There’s a world of other actors in the industry, but I’m really looking through the lens of those that fund, own, and operate these assets. So some people call them next generation IPs, independent power producers, but basically call them whatever you want. They’re the ones that own and operate these assets. And then and for them to really win in this global energy transformation underway, they really need to harness the power of digital innovations. Otherwise, you can get slaughtered in the market. The difference between smart and dumb is being killed actually and it’s that severe in returns on capital employed. Source: Peter Bance, Oxford Energy Network Talk, 4:30-5:10

What has changed is not just optimisation logic, but the need for architecture: a way to connect physics, economics, and governance coherently, repeatedly, and at scale.

From pipelines to platforms — inside the asset

Platform thinking will help explain how the flex-ops software landscape is developing.

A traditional pipeline internalises decision-making. Data flows in, actions flow out, and value is captured through tight integration and throughput. A platform does something different: it defines rules, permissions, and interfaces that allow multiple participants to interact. Aggregation creates value in yet another way—by bundling heterogeneous components into a single managed whole.

These distinctions, familiar from digital markets, are now re-emerging inside the flex-asset stack itself.

What appears to be a competition between software vendors is better understood as a competition between architectural responses to the same underlying problem: where should coordination sit once every cycle becomes a considered choice rather than a side-effect?